We’ve been slowly driving down a gravel road on the outside of the Gariwerd. We have come this way to see what will be the first indigenous Australian rock art I’ll have seen. As we pull into the car park for Bunjil’s Shelter I battle my habitual instinct to be comically irreverent and suppress the urge to make a joke about how this would be a good place for us to dump the leftover food scraps and rubbish from the camping trip we have just been on. It gets on my nerves when people make jokes during tragic parts of movies or take jokey selfies in front of stunning landscapes they have only just arrived at, so I feel my stupid joke would be disrespectful and make me the kind of jerk I hate. I know my sense of decorum is somewhat arbitrary but that doesn’t make me feel any less self-righteous about it.

The walk is short; after a two-minute tramp up a small hill covered in boulders and scraggly, dry Australian flora, we are surrounded by a landscape that is rural with patches of forest and sandstone mountain ranges in the distance. We quickly come across the rock art, painted in a shallow little cave within a huge boulder. The art is separated from us by a protective metal cage but nevertheless I am struck by it. I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t want to force myself to feel anything, like when you hold a hundred million year old fossil in your hand and try to make yourself understand, truly understand how ancient it is but all you can think about is how you’re hungry, horny and insecure about why so and so hasn’t called. But in this case, I needn’t force myself to feel something because I am struck instantly.

I’m reminded of a time at art school where we were made to do a meditative drawing exercise in the beautiful Tangatarua Marae. We were each blindfolded and then handed an object which we had to draw in our sketchbook for several hours without being able to see anything we drew. The instructor handed me a soft object, a roll of toilet paper, I laughed and cursed him but as the hours passed I found myself hurtling through swirling vortexes while simultaneously drawing them into existence. When we finally took off our blindfolds, I was disappointed and amused by how tiny and unremarkable my drawings were because they had felt immense. We discussed our individual experiences and one woman spoke of how she had spent the last half-hour sobbing because she had reconnected with mark making and was so deeply touched by it.

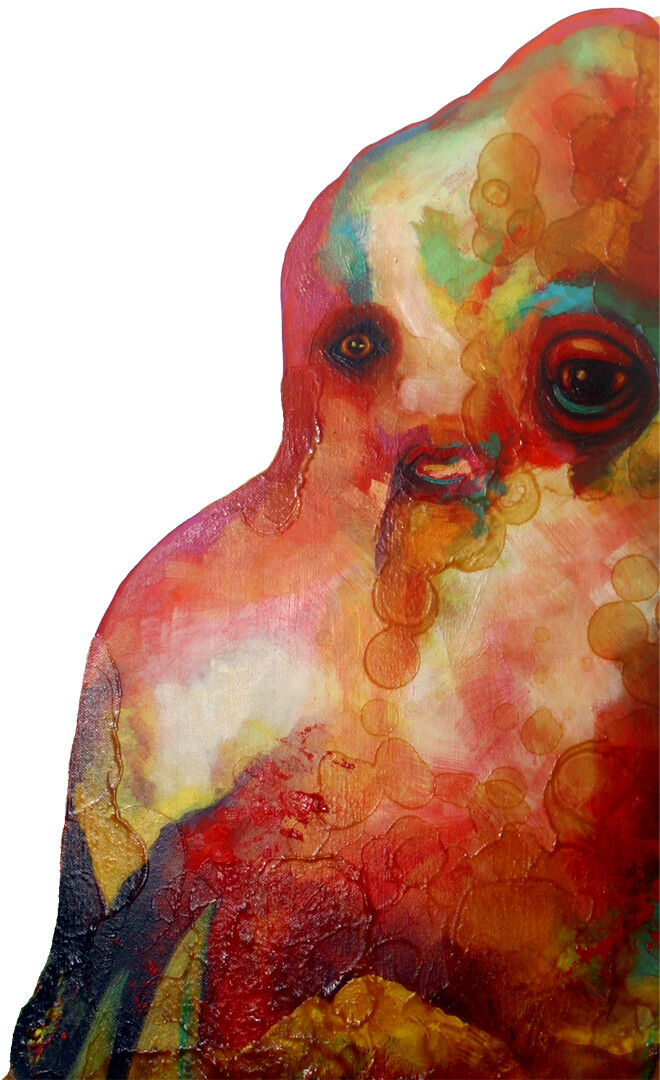

I remember that lady as I look at an artwork that I reflect could perhaps be 3000 years old. I think about mark making, how old and deep that impulse is within us. I think about how it is a means of communication through generations, an attempt at defying mortality, a method of creating and expressing meaning. I think about my own ever-present urge to make marks and how my body and my injury no longer allows me to do it compulsively. I think about how lucky I am during those times when I can pick up a paintbrush and how, to me as an atheist, art is the closest I come to religion, art is how I express angst and awe. I think about how some of the marks are from more recent European white overpainting, an attempt perhaps at preservation. I think about white paint, white people, colonialism. I think about how I can never know what was going through the artist’s mind when they painted this, I can never know if they were inspired, leaving a message or simply a bored kid killing time through the hottest hours of the afternoon.

After a while I leave that spot and start to explore the small hill and boulders surrounding it. I want to hang onto this feeling I’m having, this calm, so I walk slowly, running my hand along the boulders and feeling as if I truly comprehend the weight of them. I climb up onto one of the rocks and look out across the landscape. I begin to imagine the people who had been here before me, thousands of years before me and I feel sorrow while beholding a landscape that I now perceiv to be blighted by agriculture and scarred by roads. I find myself imagining someone a thousand years ago standing on this same boulder and surveying a land unblemished and I am uncomfortably aware of myself romanticising a past, a place and a people I will never know.

I run my hand across the lichen and observe that this particular organism looks as if it is covered in thousands of tiny, gaping baby bird maws. I observe the whiteness of my own hand and the tacky cat print dress I brought in Thailand. I think about my own whiteness and about how when I was a kid growing up in New Zealand, I thought I was Māori because most of the kids at my school were. We sung songs in Māori, we ate hangis, drew koru patterns and my grandfather was Fijian which, to a six year old, is the same thing. When I realised I was not Māori, I remember feeling strange and uncomfortable about the realisation that I was… Pākehā. I think about how I never quite felt at home in New Zealand, America or, now, Australia. Perhaps I will always slightly feel as if I am trespassing on the space of others, but how this is not a feeling that especially causes me angst anymore because it simply is. Humans are an invasive species.

I think about my tendencies to daydream and how I love places with a sense of history connected to nature. I also think about how one can navigate an appreciation of other cultures and foreign lands without colonising those places, without romanticising the other. At the same time, I think about how romanticisation is a way in which we connect to the past, the way we feel a lovely and painful nostalgia for that which once existed but which we never knew.

I think about the more recent graffiti that people have left on the boulders and which has been removed by do-gooders with scrubbing brushes. I think about the value we place on the past while considering the scrawlings people have left from our own time to be without value. I think about how I am glad that the graffiti has been removed, how I am glad that we treasure the disappearing remnants of the past and try, desperately, to preserve places of natural beauty… but how we also forget that this current time we are in is just as transient, someday there will only be fragments of this left and someday there will be nothing. We think we are separate from nature but all of this is the exact same stuff and the only thing that separates it is the meanings we assign.

I reach my hands out and feel a warm wind blowing against my skin. The air here is alive, perhaps only with the meanings I have embedded into this place but nonetheless, it is beautiful and sacred and I feel grateful. As we leave, I find myself touching the blackened stump of a tree consumed by a bushfire and whispering “thank you”.